Get in touch

- akwebster@fsu.edu

- Department of Biological Science

Florida State University

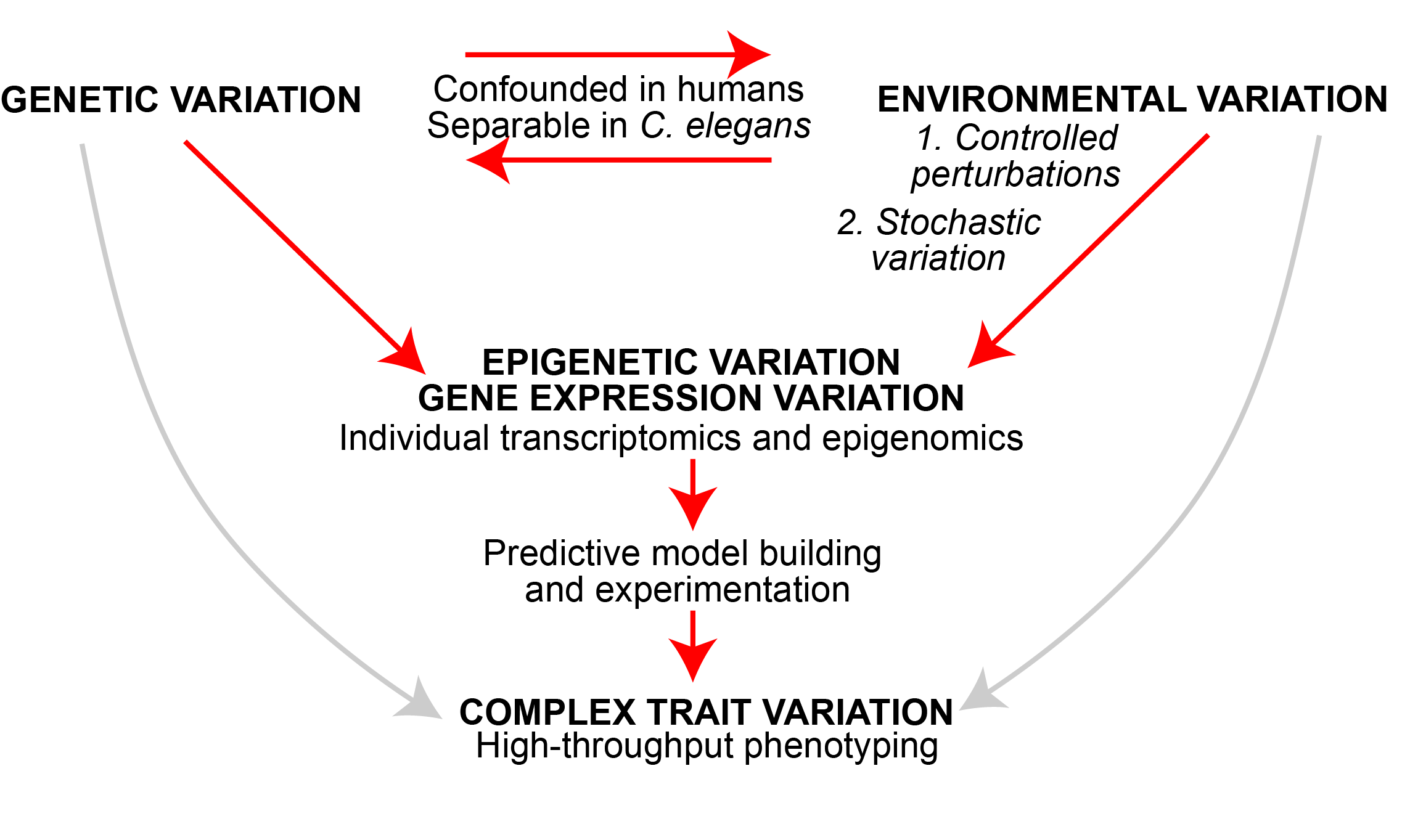

Why individuals are different from each other is one of life's fundamental puzzles. A given individual's phenotype may be driven by a combination of genetic and present environmental conditions, along with prior environmental experiences, development, or other unknown causes. The epigenetic regulation of gene expression plays an intermediate functional role between genetic or environmental perturbations and organismal phenotypes. A major goal of our research is to understand the influence of genetic and environmental variation on epigenetic and gene expression changes, and in turn, how these changes shape important traits throughout the lifespan of individuals and impact the evolution of populations. We use both experimental and theoretical approaches to address these questions. For the experimental work, we primarily use the nematode C. elegans.

The nematode C. elegans is well-suited to support research in the area of individual variation. C. elegans primarily exist as hermaphrodites (with rare males) and do not exhibit inbreeding depression. Each individual hermaphrodite can produce roughly 300 progeny in a matter of days. In the case of inbred lines, each worm produces genetically identical progeny, making it relatively easy to generate thousands of genetically identical worms. These worms are microscopic and transparent, can be genetically altered via CRISPR or other genetic engineering approaches, and can be grown in liquid or on plates. The C. elegans genome was the first animal genome to be sequenced, and it is well annotated. In addition, the nematode community has collected and sequenced many genetically-distinct wild isolates within C. elegans as well as related nematodes in the Caenorhabditis genus from around the world. In sum, both the genetic and environmental conditions across generations can be carefully controlled with this system, and the worm community has developed resources to facilitate sophisticated analysis of the causes and consequences of variation.

Many identical human twins exhibit divergent disease outcomes or have different traits, even when raised in similar environments, for reasons that remain poorly understood. What is the molecular basis of these differences? Genetic background cannot be controlled in humans or most other species, but with C. elegans, we can generate many genetically identical individuals and phenotype them for traits of interest. Using C. elegans, we are focusing on quantitative traits, especially those related to reproduction, longevity, and stress resistance. Amy's postdoc work showed that variation in gene expression across individuals is associated with differences in reproductive traits (many of these genes are shown in the adjacent figure). Gene expression patterns of multiple genes together are highly predictive of reproductive traits, and knockdown of genes confirms causality. Genes predictive of reproductive traits are also enriched for particular chromatin marks, suggesting epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Current projects in the lab are oriented toward the extension of this analysis to additional traits and assessing the causality of chromatin marks using genome engineering approaches.

Just like how changes in the genome sequence can cause average differences in traits, genetic changes can also cause changes in trait variability. Identifying such genetic differences is difficult because it requires measuring many individuals to accurately determine variability. Because we have identified gene expression variability that is linked to traits within a single genotype, current work in the lab aims to extend this to multiple genotypes so that we can understand how the sequence of the genome itself controls variability in gene expression linked to complex traits. There are a number of genetically diverse strains in C. elegans that can be used toward this end (see some of Amy's past work with these strains here). Ultimately, we aim to identify specific loci underlying this variability, which may be important for understanding the apparent randomness underlying the development of traits and diseases.

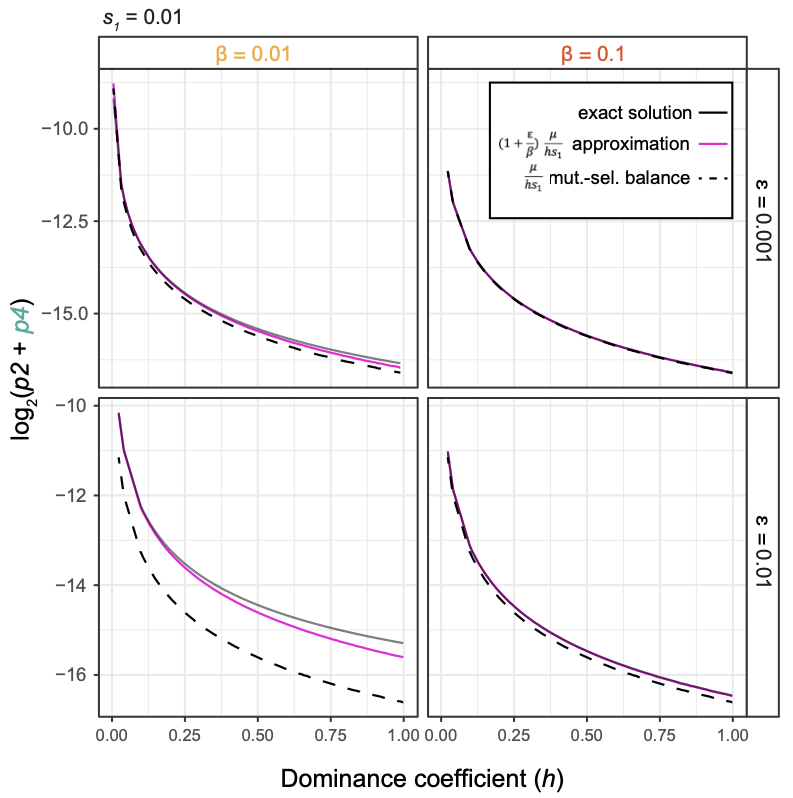

Epigenetic variants that arise randomly or in response to environmental perturbations can sometimes be inherited across generations. This raises the possibility that epigenetic variation can act alongside genetic variation to shape the evolution of populations. Epigenetic variants arise more often than genetic variants, but do not typically persist for many generations (in contrast to germline DNA mutations that are faithfully inherited). Amy's postdoc research involved building theoretical population genetic models to understand how epigenetic variants persist long-term in populations and how they interact with genetic variants. One major result of this work is that the rates at which epigenetic variants arise and persist affects the maintenance of genetic variation over time (shown in the adjacent figure). Ongoing work aims to test this result empirically using experimental evolution in C. elegans. Because worms have a 3-day generation time and known genome sequence, we can run experiments for dozens of generations and determine genetic changes. We are also interested in extending our theoretical models.

Genetically identical individuals in a shared environment can exhibit phenotypic differences due to their past environment (e.g. early-life conditions) or due to their ancestors' environment (e.g. maternal or transgenerational effects). We are interested in identifying the genes that control these effects. In addition, we are interested in how present environmental exposures cause average differences in traits and in trait variation. We are primarily focused on effects due to parental age, temperature, and chemical exposures, which have broad implications for aging, climate change, and environmental health.